Drawing the Undrawable: An Explanation from Neil and Amanda.

So that, as they say, was a thing.

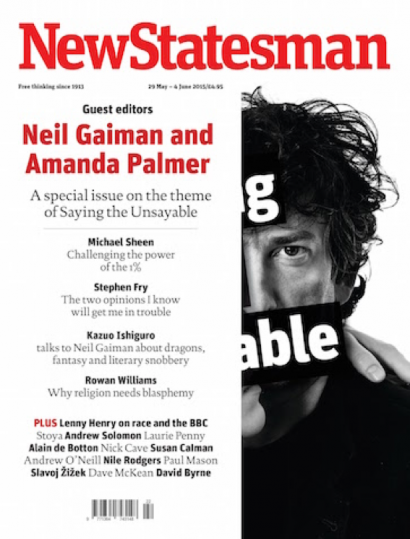

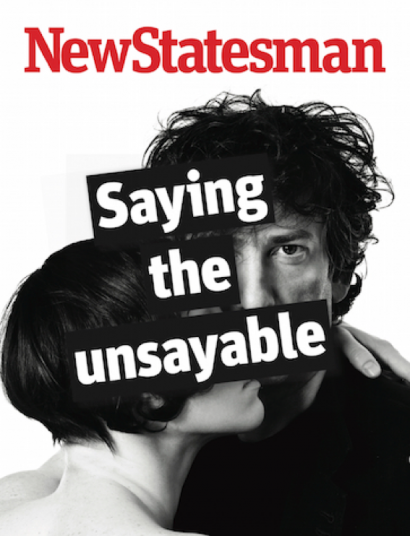

The Neil and Amanda guest-edited New Statesman came out a couple of days ago. It’s what we wanted it to be – an issue about saying the unsayable, filled with writers saying stuff. We are in it too. Everything is perfect…

Except the cover isn’t the Art Spiegelman cover it was meant to be, the one that went up online at the New Statesman site and then vanished again. It’s an Allan Amato photo of Neil and Amanda instead. A beautiful photo, with text over it. But it’s not the cover we told people we were putting out, the cover that people have been asking us about.

This is what it looks like with the flap covering the left of it:

We owe you an explanation for why this is, especially as it gets into strangely self-reflexive territory: an issue about saying the unsayable that loses its cover for reasons of, among other things, freedom of speech, human error, and whether or not you can say the unsayable. Or show the unshowable.

And the short tl:dr version of this is:

We loved Art’s cover. (So did the New Statesman.) We are really sorry that the cover wasn’t used. Art pulled it because he felt that agreements with the NS weren’t being kept, specifically, he had done a comic that he wanted in the issue, and as Guest Editors we’d assured him that wouldn’t be a problem. Communications between Art and the NS were not good: they didn’t get back to him on his questions, or, we think, understand that they were meant to include the comic. When the NS editors learned about the comic it was already too late to put it in the magazine, and when the Amanda-and-Neil-put-it-online solution failed, Art, with enormous regret, pulled his cover.

Amanda:

Of all the things we were excited to attack with this “Saying the Unsayable” issue, the cover was at the top of the list, because it posed such a great braintwister: how do you draw what can’t be said? Neil and I spent a few weeks chatting through all the various options – one of the nice things about being a musician and graphic novelist who have both been collaborating with artists for years is that we had a list of art-geniuses a mile long. Art Spiegelman won, in the end, because he was perfect for the theme. I remember seeing, in a newsstand the week after Sept. 11, 2001, the cover for The New Yorker – thinking, at first, that it was a solid black image. And then, as the issue caught the light and revealed two magically disappearing towers, painted in ghostly gloss with a single antenna thrusting through The New Yorker masthead, I knew I was looking at the work of artistic emotional genius. (click HERE to see it)

Art’s been a fighter for visual free speech for ages: his seminal graphic novel “Maus”, a profound commentary on family and nazism, has recently been banned from sale in Russia because it featured a swastika on the cover (though one could argue it was hardly “nazi memorabilia – not to mention Art has already won the argument in Germany that Maus was culturally significant enough material to allow it onto shelves). Art’s also let us crash at his apartment. So we were gleeful when Art agreed to do the cover, even though he had his grumpy doubts about the British press (we’ll get to that in a second), and I traipsed over to Soho to have a long chat with him about what we might do for an image.

For three hours, over two walks and three locations (one cafe, Art’s studio, and we stopped by to visit the artist JR: you’ll note that that gave accidental birth to the use of JR and Art’s Ellis Island graffiti/drawing collaboration in the issue), we discussed the potential for the cover, and I told Art about the fantastic writers we had on board, writing about the unsayable. I wound up getting a three hour crash-course in banned comic history, including the life and times of Fredric Wertham, Comics-burning, and the Comics Code.

In his studio, Art showed me some of his recent covers and comics following the Charlie Hebdo massacre. We batted some ideas around. An image of Me and Neil? Only if it was a really strong idea, I said. I didn’t want this being about our egos – and we had balked at the idea of just using a nice photo of us on the cover. There’s certainly nothing Unsayable about that.

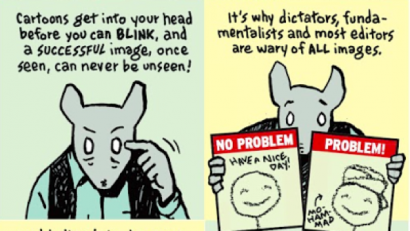

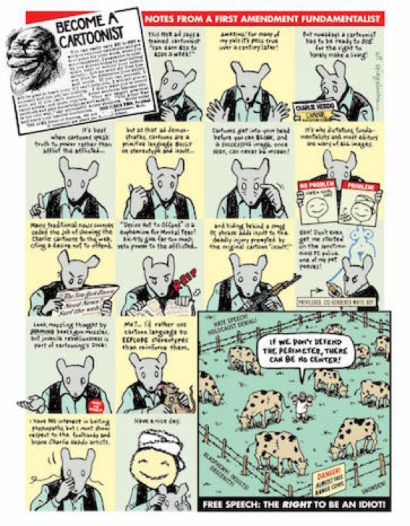

Art showed me a comic he’d drawn about what you can and cannot say as a cartoonist, which I found smart and hilarious, and hardly controversial: Notes from a First Amendment Fundamentalist. It pictured Art, shown as the mouse-headed narrator, explaining what images were for, and why editors were scared of them, preferring to show smiley faces with “Have a Nice Day” on them instead. The comic had run in The Nation in the US, in many European countries and on the cover of a german paper, the Frankfurter Allgemeine. It hadn’t been run in the UK, Art said, so we could have it as an exclusive. Brilliant, I said. Art told me the New Statesman had already passed on running it, back when Charlie Hedbo happened, not – they’d told him – on the grounds that it was controversial, but on the grounds that they’d felt they had enough Charlie Hebdo coverage. Art had been in China when the massacre happened and didn’t get cracking on this drawing until a few weeks after the main news explosion. The London Review of Books had passed on it because “they disagreed with what Art said in it”.

It was something he felt really strongly about, and he was disappointed that it hadn’t been seen in the UK. Would we run the comic as part of the issue? Neil and I both loved it — it was a comic about saying the unsayable. We let the New Statesman know, Art sent over the image of the comic, and we got to work on what we thought was the hard part, the cover itself.

(Click on it to read it at full size.)

Neil:

The phone buzzed and Art and Amanda were together in New York. We talked ideas for covers.

Art is a cartoonist: he writes beautifully and well, but his medium is pictoral, or that combination of words and pictures that become more than either alone.

“I don’t think you need me,” he said. “They could do it with just a photo of you guys on the cover.”

“We need you,” we told him.

We wanted an image as powerful as some of his iconic New Yorker covers. Art retired from New Yorker covers, mostly because he didn’t like having to negotiate or deal with magazine people, but he was willing to do it for us.

“The problem is,” he warned us, “that you can write about the unsayable, and nobody will mind. But if you draw the undrawable, you’re in trouble.”

We tell him we are game for trouble.

Ideas are discussed: Me and Amanda as Paper Dolls surrounded by the costumes we could wear, all of them evoking things different groups would find offensive. Amanda and me about to be burned at the stake, with other burnable things. The see-no-evil monkeys.

We settled on me and Amanda drowning in our own word balloons, and got Art photo-reference of us.

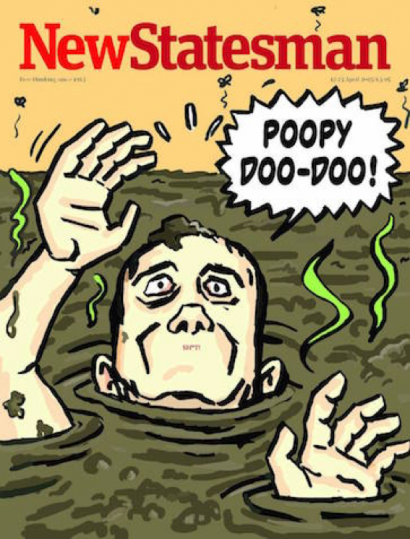

He called the next week. The word bubbles cover wasn’t working. But he had an idea: a man drowning in shit, unable to talk about what he was drowning in.

The man would be calling out baby names for shit, loudly…

Art sent us a rough of the image:

It was great, except, it wasn’t right. I showed it to Amanda.

It was a powerful image. And some days it feels like we are drowning in shit.

But…

I talked to Art after the Pen Gala, and explained my problem.

“It doesn’t say Saying the Unsayable to me,” I told him. “It says, We Are Drowning in Shit. It’s the cover to the Drowning in Shit issue.”

Art had already had another idea. He showed it to me. I took a photo of it and sent it to Amanda. She said “YES!” and we had our cover.

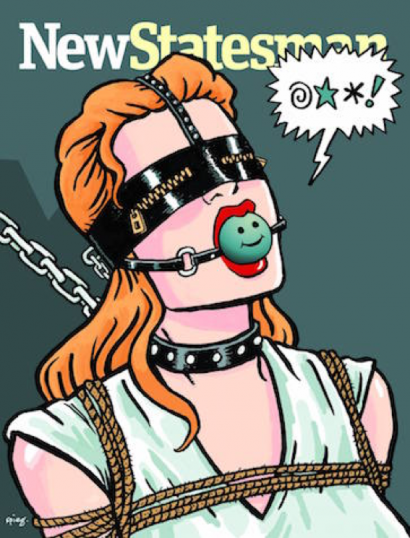

A week later, Art sent us this:

And it was perfect. Amanda was concerned people would look at it and see only a disempowered woman, not an angry woman. The New Statesmen people liked it (some of them loved it) but they were also concerned it might be misinterpreted.

We wrote a piece that was meant to go into the New Statesman talking about it:

We actually can discuss the unsayable. We are doing it here, in this issue. In that sense, “unsayable” is almost an oxymoron.

We can talk about something without actually showing it. We can discuss “drawing Mohammed”, we can write entire books if we wish about the traditions involved in representing Mohammed, the problems inherent in it, the issues of power, offense and violence involved, and nobody will try to kill us for writing it.

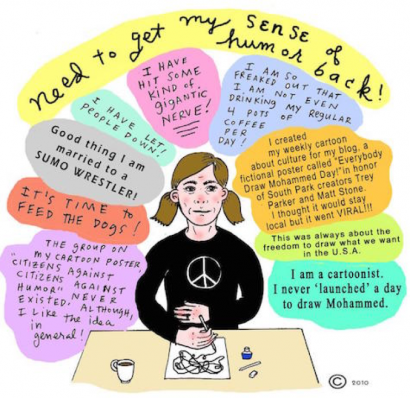

Once you draw the picture, it’s a different story: when you “draw the undrawable”. The moment that you draw a picture that shows something transgressive, even if you are simply commenting on it, you have drawn it. (In 2010 Seattle cartoonist Molly Norris attempted to satirise and comment on the issues involved in representing the prophet in a humourous way, by drawing a cotton reel, a cup, a domino, a purse, a cherry and a pasta box, each claiming to be an image of Mohammed. She was placed on an Al-Qaeda deathlist, and has been in hiding for four years.*)

* This is a simplification. At the top of the cartoon, it talked about a fictional Everybody Draw Mohammed Day, it went viral, and Molly was put on the death list. Here’s one of the last cartoons she did before going into hiding:

Images that shock or repulse us have power, in a way that words will not.

Amanda walked with artist Art Spiegelman through downtown New York for an afternoon, getting schooled in the long history of banned drawings, comics and the wake of the Charlie Hebdo assassinations. She and Art got Neil on the phone and for an hour discussed “see no evil” monkeys, people and stereotypes being burned at the stake, and how to represent offensive images without actually offending people. We wound up with the idea of Neil and Amanda trapped and drowning in their own speech bubbles. But Art wasn’t happy with it.

The first cover design he actually showed us was a glorious depiction of a man drowning in a sea of shit, unable to say the word. It almost worked, but not quite. (We worried that people would think, not unreasonably, that this was the “we are all drowning in a sea of shit” issue.)

When he sent over the sketch of an angry woman bound, “see no evil” blindfolded, but still trying to swear through the happy-face on her ball gag, we knew we had our cover.

And we stopped worrying about the cover.

Amanda:

Putting together the contents of the issue was a blast, and a tsunami of emails flooded between me, Neil, the New Statesman folks, and the various writers we were hoping would write for the issues. Some people got their pieces in within days of being asked, some people wrote thousand-word pieces only to spill tea on their computers at the last minute, missing the deadline. Some interview questions went unanswered, some people called in sick.

Some incoming material led to new inspirations, which was where we really felt the beautiful synchronicity of concocting a magazine in realtime, on a deadline. JR’s haunting Ellis Island graffiti images seemed to hunger for context about today’s heated immigration issues; we pondered who could write about that, and the New Statesman suggested we bring in Khaled Hosseini (whose work I’d read, but it would have never occurred to me). We ran into Laurie Penny in a Cambridge coffee shop and she offered to work with a writer of a piece we liked but felt wasn’t there yet. We emailed with our friend Stoya to see what her take was on the unsayable issues in her workplace, porn. I happened to be talking with two different friends on the phone when it occurred to me that they should write about what were were chatting about: both of those moments found their way into the “Vox Populi” sections. It was a lot of fun. The New Statesman folks were incredible – they caught the balls as fast as we were batting them and worked tirelessly on laying out the perfect issues. Everybody was really excited.

Two nights before the launch of the issue – the night before the final pieces of the magazine were to go to the printer so the magazine could hit the stands on time – we got a distressed email from Art. He was going to have to pull his cover, because he’d gotten an email from the magazine saying they they wouldn’t run his comic.

Because of timing, or because of the content? Timing, probably. My brain did a few frantic calculations. Had we sent it over? Had we missed it in the master list? Oh shit. Maybe. I admitted to Art that we hadn’t been the most organized editors – but we’d call the magazine right away. The worst thing that would happen was that it would miss the print deadline, but it would make it into the online version, which was, hopefully, going to see even more traffic than the printed issue, anyway. Art sighed and said he’d be happy enough with that, but he needed a promise from The New Statesman. It was 7 pm, We phoned the New Statesman. It was too late for the comic to get into print, they said. Could we run it online? They froze. Apparently, there had been a New Statesman-wide meeting and consensus that the magazine wouldn’t print any images of the prophet Muhammad. But Art’s comic didn’t depict the prophet, it depicted Art tearing off his mouse mask and revealing a smily-faced, turban-wearing… Neil and I sighed. We hung up the phone. We looked at each other, glumly. This sucked.

“Okay. What if…” I said, “you write about the evolution of the cover for the online version of the magazine, and in there, just put a thumbnail of the comic which links to the full-size version of the comic which is already up online? You could interview Art about censorship. That way the comic gets the attention it needs, the New Statesman doesn’t have to actually run it, Art will get his way, and we won’t have to lose our beautiful cover. Because honestly, the heavy irony of the fact that we’re sitting around here discussing losing the cover of our ‘Saying the Unsayable’ issue because we can’t run a smiley face with a turban on it…”

Neil furrowed.

“We can try.”

We called The New Statesman. They said they could live with that.

We called Art. He said he’d go for that.

We breathed a massive sigh of relief. Neil called Art and did an interview with him about pictures and art and censorship and why artists need to be able to do art to communicate, for the blog. Neil couldn’t work out why the Skype calls kept failing. (I was in bed on the internet, downloading things.)

But after three calls, he came to bed. We were saved.

The next morning, at 10 am, I had voicemails and texts to call the New Statesman. I gulped. We called. The peace treaty had broken down overnight. Art’s agent had put The New Statesman’s promise to run the thumbnail, with the link, in a blog written by Neil, into a contract and sent it over. They wouldn’t sign it, as they explained, if they failed to do as Art requested, he could have the whole issue pulped. They said they’d rather pull the cover. It was 11 am, and Neil and I were on a train to go and visit his family in the countryside, with phone service coming and going. We spent the train ride on the phone convinced that we could re-assemble the agreement we’d managed to put together the night before. The absolute deadline for printing the cover was 12pm.

We couldn’t do it.

By 11:45pm, it became clear that Art’s cover was going to be pulled. We started discussing, reluctantly, what could possibly replace it. The New Statesman mocked up a simple cover using the press photo by Allan Amato that was taken four years ago, with the words “Saying the Unsayable” printed across our faces. We sat in a cafe in the English Countryside that happened to have wireless and downloaded it.

“This is fucked. This is an issue about censorship, and it looks like the cover of GQ.” I said.

“We could just go all black….” said Neil. (Of course).

We sent some half-hearted remarks to The New Statesman to improve the size and placement of the text, but we didn’t have any further time to discuss it. The cover went to press.

Neil:

It was a complete cock-up. Art’s ironic prediction of a photograph of me and Amanda on the cover proved correct.

Art’s real frustration is that the British press can write about freedom of speech while at the same time having blanket policies which mean that an image like this one becomes unshowable. (In context:, Art shows us a magazine with a smiley face and turban, labelled Mohammad to show us what is a problem, and what is not. The New Statesman took it as showing an image of the Prophet, something that they had agreed amongst themselves they would never do.)

I suspect that if the New Statesman had had longer to talk amongst themselves and to think about the Art’s comic it would have made it in, but I could be wrong.

The night before the New Statesman went to press, when the agreement was that I would blog about it on the New Statesman site, I interviewed Art for the blog. He said a number of cogent things about image and cartoons, about why the UK press wouldn’t show images, like his comic, which had been on the front covers of newspapers in Germany and prominently published elsewhere in Europe. On why, in a secular society, it is vital not to bait, but to debate – and that people who use pictures to communicate needed to be able to use their pictures, as those of us who use words use their words. That there cannot be a Kalashnikov veto on what is published.

(The blog didn’t run, and as Art says, he gave the interview being still kindly disposed to the New Statesman, and he doesn’t feel that way any longer, so I’m not going to quote from it.)

Art feels angry: angry for the wasted work, and because he wants people in the UK to see his comic.

The New Statesman editors felt aggrieved, trapped between the rock of having to show an image that might, conceivably, have been interpreted as showing Mohammed in order not to lose their cover, and the hard place of their discomfort with the Wylie Agency.

Amanda and I are sad and disappointed. I’m mostly disappointed because I thought that the proposed solution (of blogging about it on the NS site, with a thumbnail of the comic that you could click on to take you to a larger image, so the comic could be seen, and in the blog Art and I could talk about the issues involved) was something that worked. I’m still sad that the New Statesman backed away from it, when it was put in writing.

It’s obvious, going back in the email chains, to see the breakdowns in communication between Art and the New Statesman and vice versa, while Amanda and I were riding the magazine guest-editor whirlwind (writers dropping out and coming back in, pieces coming to us or going directly to the NS, people we waited on for articles or think pieces or interviews until the last moment, while still trying to keep our lives and our real, paying work going). It was our cock-up as much as anyone’s: we knew he wanted the comic in and had sent it over, and didn’t actually think of it again until the end.

Neil and Amanda:

So that’s what happened, and why Art’s cover isn’t there on the cover of the New Statesman.

Running a magazine is insanely hard work, and having to deal with the crisis at the last minute was no fun for the New Statesman team, who have been supportive of us all the way, and who wound up, at the end, face to face with, and having to deal with, what is and isn’t unsayable. (And from their perspective, as they expressed it to us, it was also a freedom of speech issue: they didn’t want to run the comic, and couldn’t be pushed into it.)

But…

This is how we get into this mess in the first place. “We would, but…” “We should, but…” “We believe in freedom of the press, but…” It’s death by a thousand buts. We wanted to say the unsayable, and draw the undrawable. We ended up feeling like we’d tried, and, due to human error on our parts and on the magazine’s, failed.

We’re really, really proud of this issue, and we’re honored that the New Statesman gave us a chance to gather all these artists and writers together. We have the former Archbishop of Canterbury writing about why religion needs blasphemy, and Stoya on porn, and Michael Sheen and Hayley Campbell and Kazuo Ishiguro and Roz Kaveney and Nick Cave and…

We just wish we were as proud of the cover as we were of the content.

Have a nice day.

Neil and Amanda